Harvey reports that "prior to 1819 there was nothing in Nova Scotia that could be called a public library and little that would indicate a wide demand for books." 1 This changed rapidly over the next decade, however. By 1822, public libraries had been formed in Newport, Amherst, Yarmouth, and Pictou. Although Halifax had the Garrison Library (later known as the Cambridge Library) with several hundred volumes, and the libraries of St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church and the Wesleyan Society, the first public library in Halifax was not opened until 1823, and then only in name. The subscription price for library membership at five pounds per share and a thirty shilling annual fee was too expensive for all but the elite of Halifax.

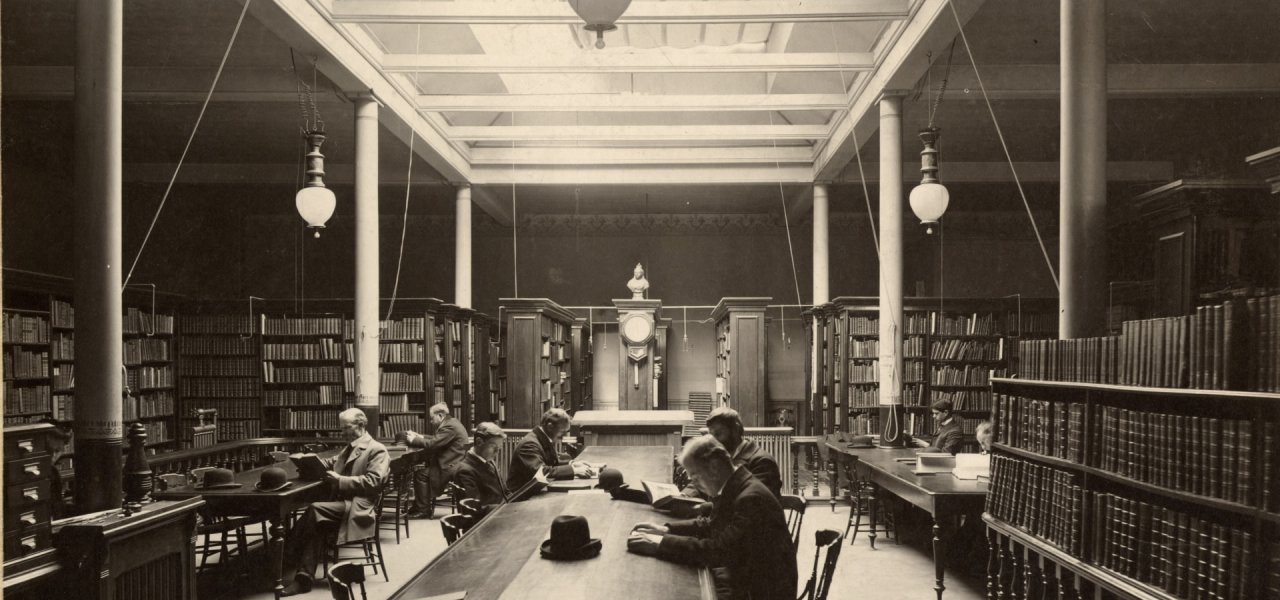

Greaves indicates that "some prominent merchants, journalists, and politicians felt that adult education should be further popularized." 2 Building upon the Glasgow experiment of 1823, the Halifax Mechanics' Library was formed in 1831. Starting with a donation of some 50 books, it had acquired some 700 books by 1834, with a circulation of some 200 items per week. The Mechanics' Library operated in Halifax from 1831 to its dissolution in 1864, when the Chief Justice purchased its holdings and presented them to the City, which gift became the foundation for the Citizens' Free Library. A catalogue of holdings is available for seven different years between 1832 and 1860, covering almost the entire period in which the Mechanics' Library was active.

Apart from the Mechanics' Library, a parallel sister organization, the Halifax Mechanics' Institute, held regular public lectures, and copies of at least some of these lectures are available. The inaugural lecture was delivered by Joseph Howe in 1832, and was followed with others ranging across such diverse topics as naval architecture, acoustics, literary composition, and elocution. This eclectic mix raises a question about the demographic and class character of the audience for the Institute's lectures and of the users of the Library. The original Glasgow model was aimed at the upper end of the working class (mechanics as skilled workers), and, as Patrick Keane suggests, this movement in early adult education aimed at the inculcation of morals, the emancipation of the working classes, and the promotion of industrial progress. However, while it may have had some resonance in the industrializing society of England, Nova Scotia was still organized around a mercantile and trading economy with consequently lower skill requirements needed from the working class. George Young, who founded the Novascotian newspaper in 1824, suggested as much in an editorial in 1827:

a blacksmith can heave a sledge without being able to calculate its momentum - that a carpenter can drive a nail, although he is ignorant of all the doctrine of direct and oblique forces - and the tailor may cut a 'Blutcher coat' to please a sixfitted dandy, although he has never heard of the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle, or learned to ascertain the quality of cloth contained in a circle of any given diameter. 3

Young's position turned out to be all too prescient. Contemporary scholarship on the Halifax Mechanics' Library supports his assessment. 4 Patrick Keane suggests that in terms of its working class raison-d'etre, "the Halifax Mechanics' Institute was fundamentally a failure." 5 Karen Smith confirms that the Library served "the needs of an emerging middle class." 6 Martin Hewitt extends this analysis in his study of the Maritimes institutes with a perceptive summary:

Young's position turned out to be all too prescient. Contemporary scholarship on the Halifax Mechanics' Library supports his assessment. 4 Patrick Keane suggests that in terms of its working class raison-d'etre, "the Halifax Mechanics' Institute was fundamentally a failure." 5 Karen Smith confirms that the Library served "the needs of an emerging middle class." 6 Martin Hewitt extends this analysis in his study of the Maritimes institutes with a perceptive summary:

In Britain, the mechanics' institutes were the product of an industrial society, and need to be analysed within this context - in the Maritimes the institutes were promoted by a producing-class seeking the social and political power with which it could obtain greater economic status. 7

In short, the Mechanics' Library and the Institute were only nominally about the mechanics.8

Action Plan

The question for our purposes, therefore, is what were the aspiring classes reading. This question can be advanced through an analysis of the catalogues of holdings. Transcription of several catalogues has now been completed, and some categorization and analysis has been conducted. Work is currently focussed on making these records ready for online viewing, analysis, and input. Our intern program is supporting work in this area.

------------------------

Endnotes

-

D. C. Harvey "Early Public Libraries in Nova Scotia." The Dalhousie Review: Vol. 14, No. 4 (1934-35), 430. Harvey was paraphrasing Lord Dalhousie's claims, but Fiona Black has demonstrated that these were over-stated and that Halifax merchants did stock a wide variety of books available for sale or loan in the absence of public libraries. See Fiona A. Black, " 'Advent'rous Merchants and Atlantic Waves': A Study of the Scottish Contribution to Book Availability in Halifax, 1752-1810," in M. Harper and M. Vance, eds., Myth, Migration and the Making of Memory: Scotia and Nova Scotia, c. 1700-1990 (Halifax: Fernwood, 1999), 175-176.

- Susan Greaves. "Book Culture in Halifax in the 1830s: The Entrenchment of the Book Trade." Epilogue, Vol. 11 (1991), 3.

- Nova Scotian, 16 August, 1827, quoted in Patrick Keane, "A Study in Early Problems and Policies in Adult Education: The Halifax Mechanics' Institute." Histoire Sociale/Social History, Vol. 8, No. 16 (1975), 260.

- In her study of literary societies of nineteenth-century Ontario, Murray comments on the experience in Upper Canada: "Upper Canada provides few or no examples of the sorts of societies early established in Philadelphia and New York, for example, which were based on English or European models of the eighteenth century: the 'literary and philosophical' model or the antiquarian model. Nor - although such societies clearly were a spectre in the pre-rebellion years - do there appear to have been the sorts of reading societies which functioned as (often sub rosa) centres for political information and theory and which developed in to the pre-revolutionary Committees of Correspondence. I have not discovered, among settlers of European descent, the women's reading parties, study circles, or 'conversations' of the kind to be encountered in early Boston, for example. The Mechanics' Institute movement appears to have been of far greater importance in early Ontario, both as a model for societies as it fulfilled many of the functions performed by the lyceums of the United States. (pps. 157-158). Heather Murray, Come, bright Improvement! The Literary Societies of Nineteenth-Century Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002). The Lyceum Movement derived its name from its Athenian inspiration. Stambler concludes that it was "a landmark in the history of adult education" (p. 184), but there is little evidence that it served the working classes. Leah G. Stambler, "The Lyceum Movement in American Education, 1826-1845," Paedagogica Historica, 21, No. 1 (1981), 157-185.

- Keane, op cit, 271.

-

Karen Smith, "Early Libraries in Halifax." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society: Vol. 7 (2004), 12.

- Martin Hewitt, The Mechanics' Institute Movement in the Maritimes, 1831-1889. Master's Thesis (University of New Brunswick, 1986), 283. In Britain, membership of Mechanics Institutes also became increasingly professional and middle class, but, nevertheless, they retained their focus on working class education. See Martyn Walker's " 'For the last many years in England everybody has been educating the people, but they have forgotten to find them any books': The Mechanics' Institutes Library Movement and its Contribution to Working-Class Adult Education during the Nineteenth Century," Library & Information History, Vol. 29 No. 4 (November 2013), 272-286.

- Material for this sketch has been drawn from the paper by Paul Armstrong, "The Cultural Awakening of Early Nineteenth Century Irish Catholic Halifax" (CCHA Historical Studies: Vol. 81, 307-328; 2015).

Anna Leonowens is known in Nova Scotia as one of the organizers of the Victoria School of Art (now NSCAD University) in 1887. She subsequently became involved in organizing the Women's Suffrage Association, where she became the first President. Although Anna was not to live to see it, the political coalition behind women's suffrage was eventually successful with the passing of the Nova Scotia Franchise Act of 26 April, 1918.

Anna Leonowens is known in Nova Scotia as one of the organizers of the Victoria School of Art (now NSCAD University) in 1887. She subsequently became involved in organizing the Women's Suffrage Association, where she became the first President. Although Anna was not to live to see it, the political coalition behind women's suffrage was eventually successful with the passing of the Nova Scotia Franchise Act of 26 April, 1918.